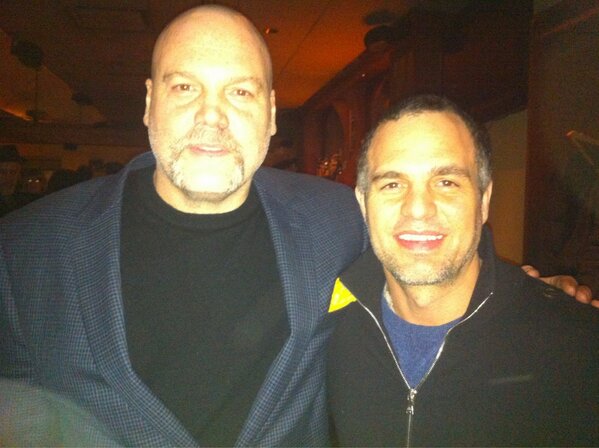

Mark Ruffalo and Vincent D'Onofrio at the #Clive Opening Night After Party. pic.twitter.com/CrXFjlX9

Ethan Hawke’s hair is bleached Billy Idol blond. His attitude is darkened to bleak, nihilistic black.

The choices are fitting for “Clive,” a wearying new play Hawke directs and stars in. He plays a wasted ’90s rocker who’s a serial deflowerer and dumper of women.

When one of those girls searches post-coitus for her dress, Clive sneers: “Here. I found it on the floor, right next to your virginity.”

Sweet.

Clive is such a general-purpose creep (and, eventually, murderer) that his inevitable demise inspires only indifference. Or as characters in the play put it: “A rat is dying in the gutter. So what?”

That damning little question echoes the impression left when all is said and done in this show by the ever-uneven New Group.

So what?

The puny impact is dismaying, since the full-length one-act by Jonathan Marc Sherman, who also acts in it, is “based on, inspired by and stolen from” Bertolt Brecht’s first play, “Baal.”

In 1923, at its premiere in Germany, Brecht’s work was deemed so provocative that it was closed down after one performance.

Too-hot-to-handle has cooled considerably 90 years later. The most intriguing thing about “Clive” is Derek McLane’s striking set, which comprises doorways, beer cans and baubles. But there’s no sense of danger or real daring or sharp commentary.

There is lots of Acting with a capital A. And Posing, with a capital P. Hawke, who strums a guitar and sings a bit, strikes plenty of those poses. Ditto castmates including Vincent D’Onofrio (“Law & Order: Criminal Intent”), as Clive’s burly buddy, Doc, and Zoe Kazan, who plays a couple of doomed conquests.

The outsize acting goes with this theatrical territory. Brecht isn’t about slice-of-life subtlety and dramatic illusion. He doesn’t reflect life, but holds funhouse mirrors up to it. Characters utter stage directions, like “I’m sobbing uncontrollably now.”

The bare-naked Brechtian approach to theater can create its own rules and a fascinating world. But not here. Unlike the magnetic bad-boy seducer at its center, “Clive” has no pull.